When designing engaging gameplay, we often start from a singular idea or scenario. Something that is intentionally vague to allow us to explore the idea from different angles. There might be statements like “combat is tense and dangerous” or “navigating the catwalk feels unsteady”, but how can we achieve those experiences consistently across the game? How can we say what it was, on the design side of the equation, made each challenge feel a specific way, and how can we replicate that and identify the factors involved to achieve different levels of intensity in that particular situation?

While trying to answer this question for myself in a way that would provide a reliable set of tools to reproduce and vary any given experience, I began formulating this framework based on my past experiences, various other frameworks I had used or been exposed to and the issues I had with their approaches. The result is an evolution of previous gameplay frameworks I’ve used and one that I’ve found to work well.

This framework breaks down player competencies into categories called challenge types, which are then used to formulate gameplay challenges based on the game’s mechanics.

Challenge Types & Vectors#

A challenge type is a collection of related axes, referred to as vectors, that are used to challenge a particular player competency or skill during gameplay. This gives us both measurable and defined sets of variables to work with, but also a common language to use as we discuss, evolve and tune gameplay challenges throughout development.

Challenge types are also classified by whether they present primarily cognitive (relying on a conscious mental effort to understand) or physical (relying on a level of manual dexterity) actions to execute. Most challenge types described here are a mixture of both.

Challenge types can be divided into 6 categories:

Planning#

Cognitive

Requires players to formulate an approach in advance, then test that approach in gameplay

Example: Observe the path a guard patrols and choose if, where and when to engage or avoid them.

| Vector | Scale |

|---|---|

| Concept | Conventional <—-> Abstract |

| Comprehension | Easy <—-> Difficult |

| Comprehension | Low <—-> High |

Timing#

Cognitive, Physical

Tests players ability to measure, predict and react to periodic gameplay events

Example: Avoid being hit as you move past an object that rises up and crashes down regularly

| Vector | Scale |

|---|---|

| Window | Short <—-> Long |

| Frequency | Low <—-> High |

| Regularity | Regular <—-> Irregular |

Navigation#

Cognitive, Physical

Challenges spatial, environmental navigation skills across a variety of vectors

Example: Traverse a path across rooftops in a city without falling

| Vector | Scale |

|---|---|

| Space | Conventional <—-> Abstract |

| Dimensions | 1 <—-> n |

| Constraints | Limited <—->Open |

Precision#

Physical

Gameplay challenge requiring specific, precise inputs and actions in gameplay

Example: Use a sniper rifle from a tower to take out a target

| Vector | Scale |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 1 <—-> n |

| External Pressure | Low <—-> High |

Reflex#

Cognitive, Physical

Challenges based around unexpected or unplanned reactions during gameplay

Example: Avoid being hit by a previously unseen hazard or opponent when it suddenly appears

| Vector | Scale |

|---|---|

| Window | Short <—-> Long |

| Dimensions | 1 <—-> n |

| Comprehension | Easy <—-> Difficulty |

Social#

Cognitive, Physical

Challenge players’ ability to coordinate, cooperate and communicate

Example: In order to move a crate, one player must push while another pulls at the same time

| Vector | Scale |

|---|---|

| Communication | Low <—-> High |

| Cooperation | Low <—-> High |

| Competition | Low <—-> High |

📝 Note: In some cases the vectors may share names or axes, however they are to be considered within the context of the individual challenge type. Additionally, while some axes are listed, you are free to alter the list based as it pertains to the constraints of your own project and design proclivities.

Selecting Challenge Types#

A gameplay challenge can include one or more challenge types, however a good rule of thumb is not to exceed three, except in special cases, due to the increased demands on player comprehension and gameplay ability with each added challenge type. When adding more challenge types, consider keeping their vectors lower than the initial or primary challenge types you started with.

In general, fewer is better. This improves player clarity in expected action and allows for a clearer impact when modulating challenge vectors or potential addition of another challenge type to present an experience that is more or less intense.

Linked Challenge Types#

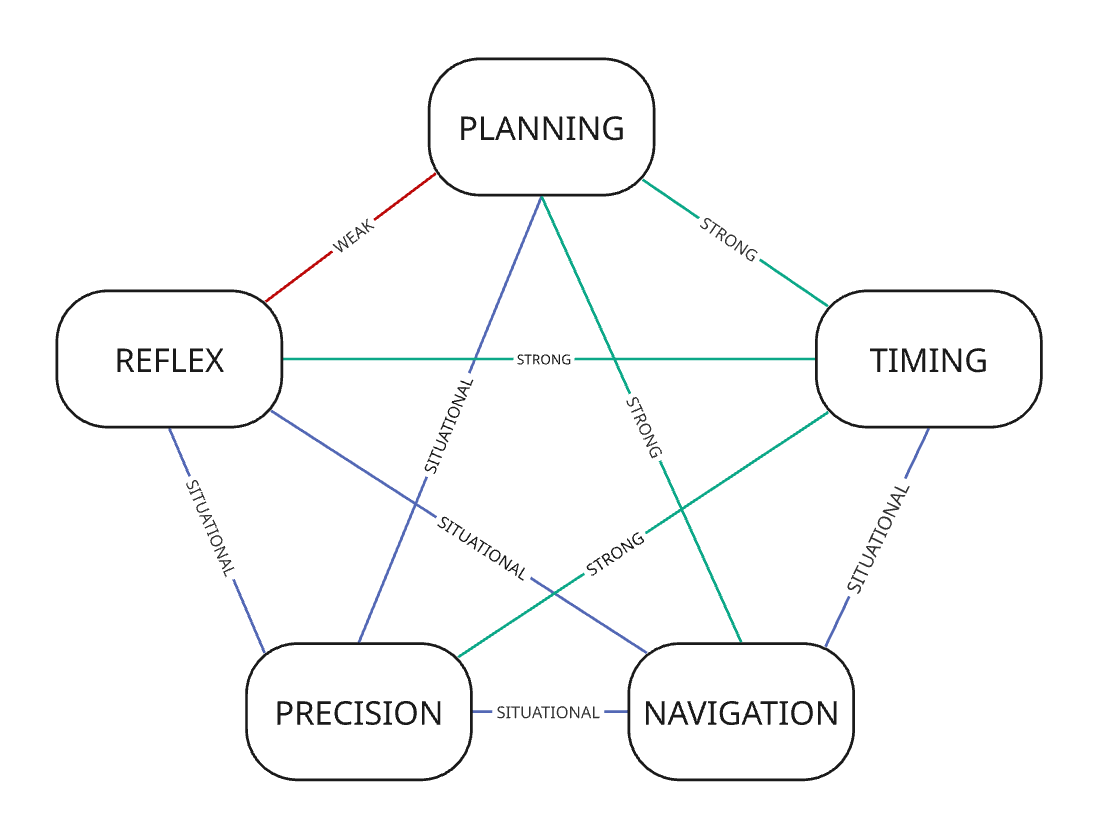

Not all challenge types work naturally together. While some do, most are situational and one in particular is weak due to its contradictory nature.

Strongly Linked challenge types are natural, expected pairings of gameplay challenges, such as Planning and Timing, which can be used to observe and understand a series of timed hazards. Note that when executing the action, Navigation often becomes part of the challenge, which is strongly linked to planning, and situationally linked to timing.

Situationally Linked challenge types work in specific scenarios, but may not in others. Combining Precision and Navigation can result in navigating a falling hazard via a narrow path, but these are much more limited use ingredients that require highly specific setup and place heavier demands on the level layout in a way that strongly linked challenges often do not.

Weakly Linked challenge types are not natural pairings and often place conflicting demands on the player. As such they are commonly used as complications, interruptions or evolving gameplay situations like unexpected waves of additional opponents. Planning and Reflex are generally opposing and as a result any plan the player makes is invalidated by the reflex requirement. This should be used sparingly as it can easily result in unsatisfying or frustrating gameplay, but when done correctly can bring a surprise factor that makes the player readjust their plan on the fly.

What about Social?#

You may have noticed that Social isn’t included in the relationship diagram. This is because Social is a unique challenge type that acts as a modulator on top of all other challenge types. As its focus is around communication, cooperation and competition with other players, it can work with all other challenge types that typically face a single player, as it represents another dimension of challenge.

Creating Gameplay from Challenge Types#

So, that’s a lot of theory, but how do we turn all this into something that describes a real playable experience?

To create a gameplay challenge from the list of challenge types, you need to consider what the core experience of your game is intended to be and decide which types you want to use.

Let’s use a simple example: A shooting gallery

For those unfamiliar, a shooting gallery is a game, typically found at fairs and carnivals, where a player stands still and shoots or throws objects at a series of moving targets.

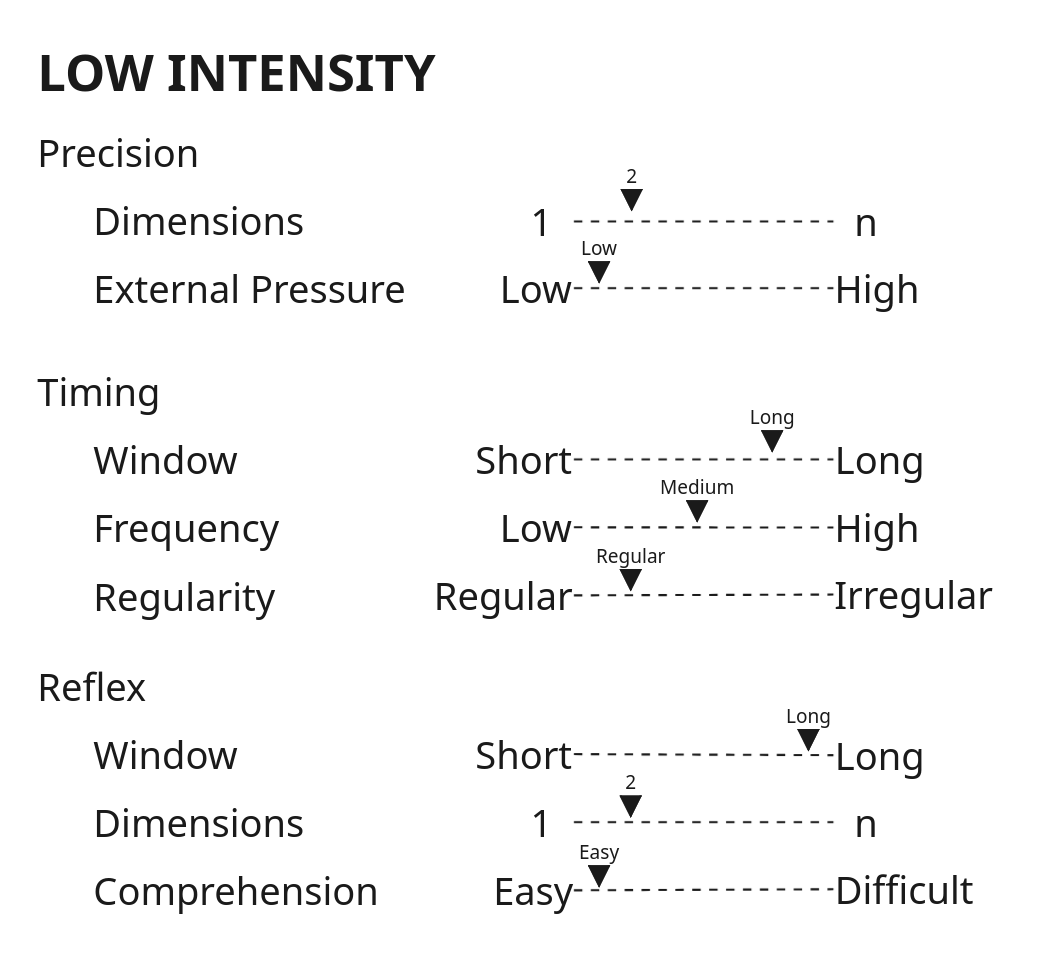

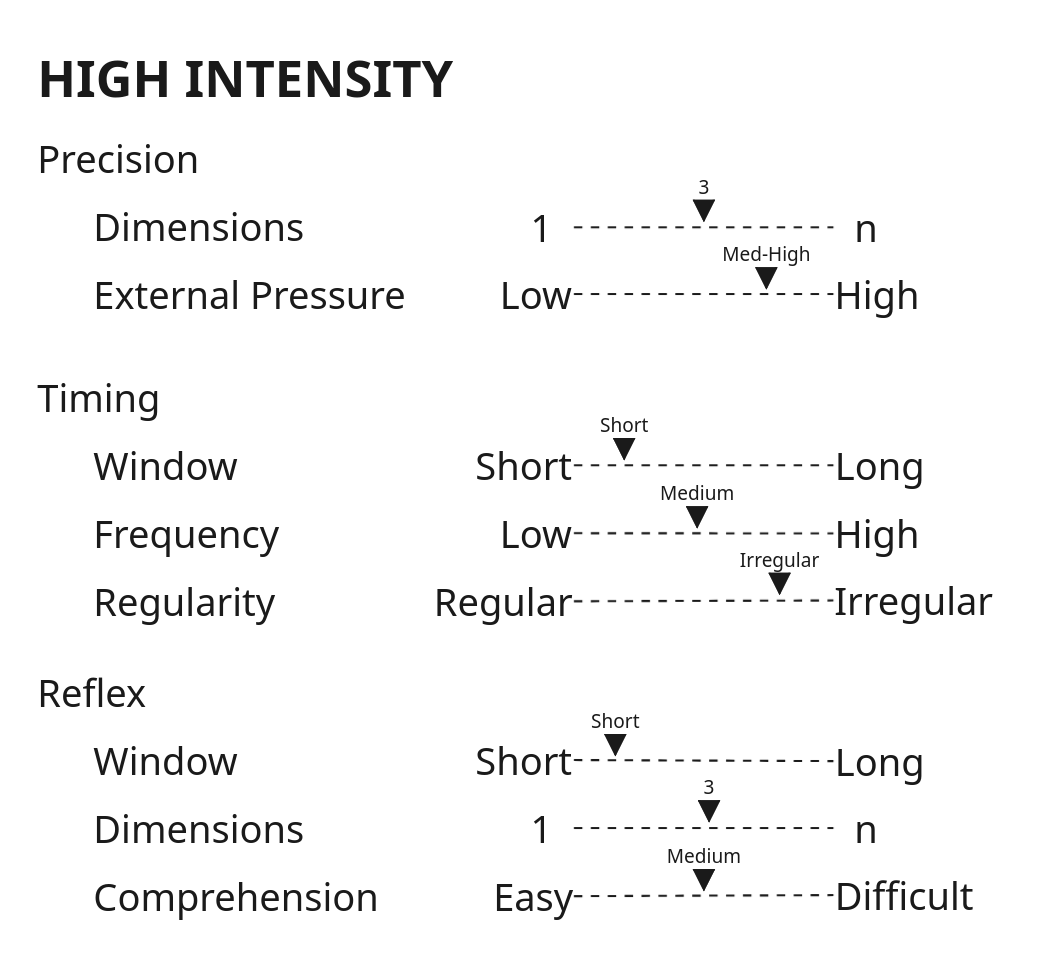

To describe our challenge we’ll use precision, timing and reflex to give us the tools we need to create a challenge that can vary the level of intensity.

By limiting the dimensions in the challenge to 2, all targets will appear at the same depth and that we’re eliminating any idea of projectile drop off. We’ve also kept external pressure low, meaning there are no distractions or interfering elements. The appearance of targets is regular, remaining for a long time, making them more predictable and generous to have a shot at. There are also few events that require player reaction (such as new targets appearing unexpectedly), but the windows are long to allow for slower reaction times. This makes for a fairly low intensity challenge that’s good for teaching a player how the mechanics work.

By modulating the vectors for each challenge type we can now ramp up the intensity of the experience. We introduce a 3rd dimension which means we will have projectile drop off and targets that can appear at various distances. Targets now appear quickly, for a short duration and at intervals that are irregular. We can also add in some external pressure - perhaps an NPC beside you jostles you, briefly disrupting your aim.

The Player-System Interaction Loop#

Observe, Consider, Act#

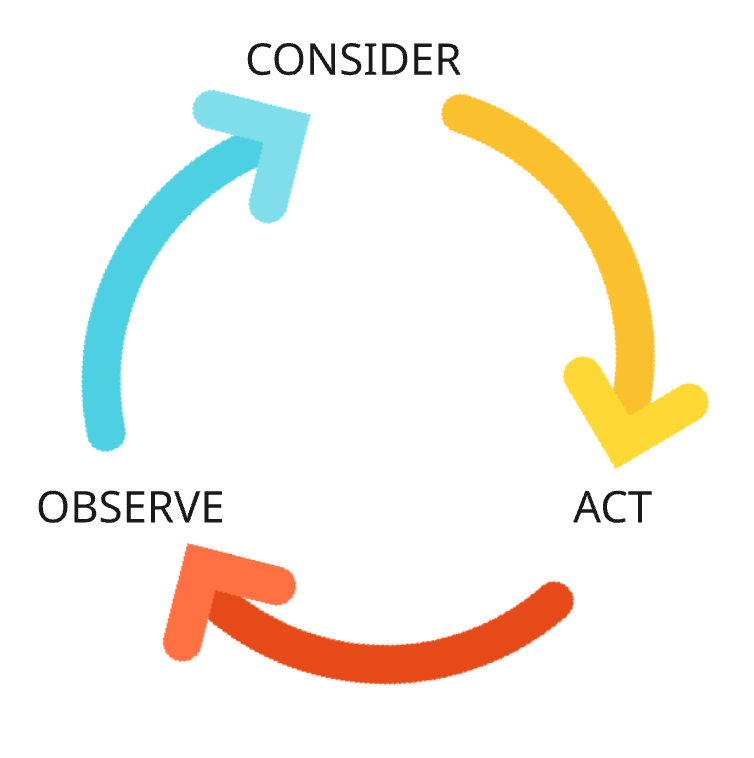

When crafting gameplay challenges, remember the player’s ongoing internal loop while interacting with the game. Every player must complete this full cycle at least once every time an event or stimulus in the game occurs. Not allowing enough time for this cycle to complete results in what appears to be noise in the game - events occurring that the player either cannot understand or respond to within the time provided.

Similarly, if events in the game occur too slowly or infrequently, players disengage as they are spending too much time in this cycle between events.

Satisfying gameplay occurs when the game modulates how often players must complete this internal loop in response to game stimuli.